Well, OK, I admit it, the picture right above is NOT Edmund. It’s just an image of a young knight, which is what Edmund was at the time of his death. The trouble is, what did Edmund of Rutland actually look like? Another giant like his elder brother Edward IV? Or…smaller and more delicate, like his younger brothers, George of Clarence and Richard III? Well, certainly as Richard III was, and it is now suggested that George was the same. (To read more about this, click here.)

Back to Edmund. First, a little background to his life and premature death. Edmund Plantagenet, Earl of Rutland, Lord Chancellor of Ireland, descended paternally from Edmund of Langley, youngest-but-one son of King Edward III. He was born at Rouen on 17th May, 1443 (574 years ago this month), and besides his English title, had an Irish one, Earl of Cork. His father was Richard Duke of York, Protector of England and supposed heir to the English throne. His mother, Cecily Neville, was a daughter of Ralph Neville, Earl of Westmorland.

I will not go into the details of York’s claim to the throne, suffice it that the House of Lancaster was seated there but King Henry VI was weak-minded and ineffectual, and York (rightly) disagreed with his right to the crown. Henry’s fierce queen, Margaret of Anjou, was certainly not weak-minded, and she had a seven-year-old son to protect, Edward, Prince of Wales. She had no intention of endangering his eventual succession, and in 1449 York was appointed Viceroy of Ireland, and thus was (for the time being) safely out of the Lancastrian way. York’s second son, Edmund, Earl of Rutland, was appointed Lord Chancellor of Ireland and went with his father.

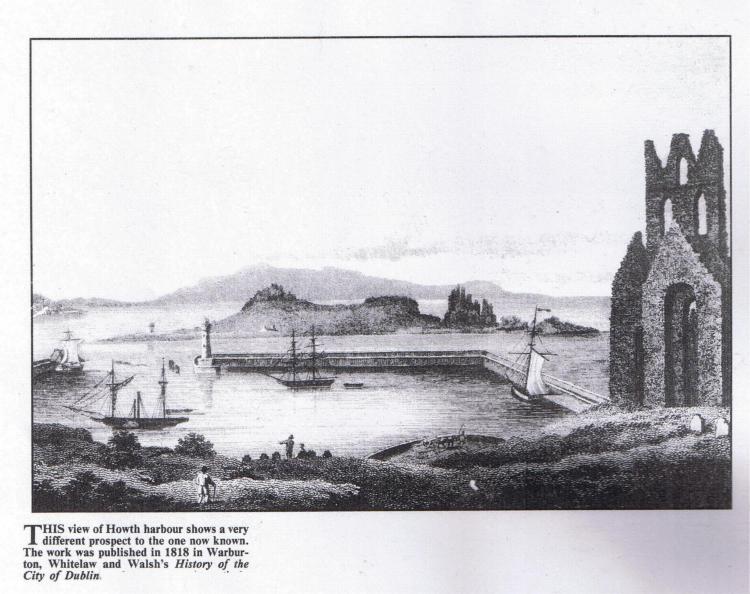

In July 1449, York and Edmund, together with York’s pregnant duchess (on 12th October she would give birth to George, Duke of Clarence), set sail for Howth, then the chief port of Dublin. They landed on 14th of the month. York soon gained the appreciation of the Irish, as well as the resident English, and the House of York was to retain that land’s support.

Not all York’s children went with him to Ireland, for his eldest son and heir, Edward, Earl of March, was holding Calais with York’s brother-in-law, Richard Neville, Earl of Warwick. The great Kingmaker. At that time Warwick supported York’s claims. It would not always be thus, of course.

Edward and Warwick raised an army and invaded England to defeat the Lancastrians at the Battle of Northampton.

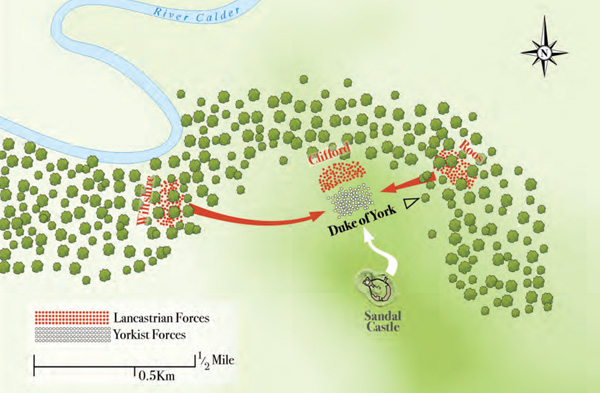

King Henry was captured, and London fell into Yorkist possession. York returned from Ireland with Edmund, and was reaffirmed as heir to the throne. The Yorkist ascendancy was soon imperilled, however, and York and Edmund found themselves trapped in Sandal Castle, near Wakefield.

They and a mere 5,000 men were besieged by the Lancastrians with 20,000 men. Help was on the way from Edward, but although York was urged to stay tight, he insisted on going out to give battle. There are varying reasons given for his decision to fight, one being that he was convinced he had enough friends in the opposing army who would come over to him. If this reason is true, he was wrong. If he’d held back, we might have had a different Richard III! And our Richard III would have been Richard IV.

The following is taken from The Lives of the Lord Chancellors and Keepers of the Great Seal of Ireland: From the Earliest Times to the Reign of Queen Victoria, Volume 1, by James Roderick O’Flanagan. The illustrations are my insertions. O’Flanagan (1814-1900) wrote a great deal about Irish history, and may have had access to a source that gives the description of Edmund. Or it might be his own invention, of course. One cannot always tell with writers of the 19th century.:-

“…On the eve of Christmas, December 24, 1460, the Duke’s army marched out of the castle and offered the Lancastrians battle. By the side of the Duke fought his second son, the young Chancellor of Ireland, whose years had not past their teens, but who, under a fair and almost effeminate appearance, carried a brave and intrepid spirit. The forces of the Queen resolved to annihilate their audacious foes, and soon the duke found how little reason he had to hope of finding friends in the camp of Queen Margaret. The historian Hume says,1 ‘the great inequality of numbers was sufficient alone to decide the victory, but the queen, by sending a detachment, who fell on the back of the Duke’s army, rendered her advantage still more certain and undisputed. The duke himself was killed in the action; and when his body was found among the slain the head was cut off by Margaret’s orders and fixed on the gates of York, with a paper crown upon it, in derision of his pretended title.’

“…The fate of the young Chancellor was soon over. Urged by his tutor, a priest named Robert Aspell, he was no sooner aware that the field was lost than he sought safety by flight. Their movements were intercepted by the Lancastrians, and Lord Clifford made him prisoner, but did not then know his rank. Struck by the richness of his armour and equipment, Lord Clifford demanded his name. ‘Save him,’ implored the Chaplain; ‘for he is the Prince’s son, and peradventure may do you good hereafter.’

“….This was an impolitic appeal, for it denoted hopes of the House of York being again in the ascendant, which the Lancastrians, flushed with recent victory, regarded as impossible. The ruthless noble swore a solemn oath:— ‘Thy father,’ said he, ‘slew mine; and so will I do thee and all thy kin;’ and with these words he rushed on the hapless youth, and drove his dagger to the hilt in his heart. Thus fell, at the early age of seventeen, Edmund Plantagenet, Earl of Rutland, Lord Chancellor of Ireland…”

1Hume’s History of England, vol iii, page 304.

The above, in a nutshell, is the life and death of Edmund Plantagenet, the York brother who is mostly forgotten.

I am intrigued by the description of Edmund as being of a fair and almost effeminate appearance. Given the similar description of Richard III as being delicate with gracile bones, and the fact that he was certainly handsome without being rugged, I am forced to wonder if Richard wasn’t the only brother with those attributes. I know ‘fair’ doesn’t necessarily mean blond—more likely ‘good-looking’—but ‘effeminate’ (rightly or wrongly) presents us with a definite type of appearance. Edward IV may have been 6’ 4”, but was he the only tall brother? Richard would have been 5’ 8” if it were not for his scoliosis, and that was a good height for the 15th century.

We’ve had speculation about the height of George of Clarence when compared with Richard (George may have been smaller), but what about Edmund of Rutland? Yes, he could have been 6’ 4” and still be effeminate, but I’m inclined to doubt it. Comment was made about Edward’s height. If Edmund had been like that, surely he too would get a mention? I had never seen a description of Edmund before, apart from Edward Hall’s Union of the Two Noble and Illustre Famelies of Lancastre & Yorke: ‘While this battaill was in fightyng, a prieste called sir Robert Aspall, chappelain and schole master to the yong erle of Rutland ii. sonne to the aboue named duke of Yorke, scace of y age of. xii. yeres, a faire getlema, and a maydenlike person….’ Just what might ‘maydenlike’ actually mean? Young? Virginal? Like a girl? All three?

In 1476, the bodies of both York and Edmund were moved to Fotheringhay, and the magnificent church that honours so many members of the House of York.

And now a curiosity, which may or may not be actually connected with Edmund, beyond his name and title. On the other hand, perhaps it’s another indication of his physical appearance.:—

Medieval silver vervel / Circa 1440-1460 |/ A silver hawking leg ring or vervel inscribed ‘+Earle of Rutland’ in derivative black letter script, for a female merlin or sparrowhawk (due to the youth of Edmund Plantagenet who died aged 17). Silver, 0.56g, 8.81mm.

Might a female merlin or sparrowhawk be a reference of Edmund’s looks, not simply his youth? Equally, it might not indicate any such thing, of course, but if the ring is dated to circa 1440-60 (and if the inscription is contemporary), the maker could certainly have known/seen him. But the inscription does not look 15th century to me. I’m no expert, though.

And finally, the novelty of a ‘conspiracy theory’ about Edmund’s death (or survival!) go to https://doublehistory.com/tag/edmund-earl-of-rutland/.

Well, Edward IV may have been tall and strong, but his face certainly doesn’t look rugged by any means in any of his portraits, with tiny heart shaped mouth and round smooth face. And the pretender popularly known as “Perkin Warbeck”, who was said to resemble Edward a lot, which can probably give us an idea of what young Edward looked like, also definitely doesn’t look rugged or manly in his portrait.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Agreed, but I have never seen him described as effeminate or maidenlike. (Hm, Heaven knows when Edward IV could last have called himself a maiden!) I am just left with the strong impression that Edmund was more like Richard (and possibly George) than the oldest brother.

LikeLiked by 1 person

After Elizabeth Tudor ordered that the tombs of the second and third Dukes of York be recreated in the Church of St. Mary and All Saints that Duke Richard and Cecily were entombed on one side of the alter and Duke Edward on the other. I have never seen any definite article as to where the Earl of Rutland is buried. Are his remains still in the choir or is he buried with his parents? Any help on this matter is appreciated.

LikeLike

Ask Mike Ingram, I think he has a thought on this.

LikeLike

I’m sorry, Gary, I cannot answer your question.

LikeLike

According to Royal Tombs of England, Mark Duffy, Richard and Cicely lie north of the high alter and Rutland and Edward Duke of York to the south.

LikeLike

Thanks sparkypus.

LikeLike

Edmund was buried in one of the side chapels. The spot may lie outside the present church walls.

Enjoyed this article greatly, as the comments about Edmund’s appearance seem to tally with Richard’s own gracile frame and quite refined facial features (he has a very light brow bone although he has a masculine jaw.)

LikeLike

I think I would like to know the source of the quote before speculating. Victorians had a propensity to describe various historical persons in accordance with their own view of them or their particular fates. However, given that Richard was described by the scientists who examined his bones as gracile, it is possible that Edmund was also.

If it turns out that Edmund, George and Richard were all ‘slight’ figures, it serves to point to the fact that Edward was exceptional – hence the rumours of his supposed illegitimacy.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Then again, Margaret was a big girl, nearly 6′ tall by some records, and no one seems to have questioned her birth. Genetics can play funny tricks.

LikeLiked by 4 people

Great article, I research Edmund a lot, because I feel like he’s been kind of ignored, and his story seems so tragic, as he was very close in age to his brother, King Edward IV. I think I actually am the one who found the painting you have on here, which then got put on Wikipedia, as I found that painting in Pennsylvania Museum of Fine Art, by searches on there, and then after I put it up on my ancestry tree, tons of saved it, and the next I know, it’s on Wikipedia as the main profile pic. But I’ve researched a lot of primary sources about him, including letters he wrote while growing up with his brother, Edward IV, at Ludlow Castle, where it is obvious they were very close, and shared a disdain for their militant tutor, who they’d complain about to their father. What’s the most tragic, is he was only 17 when he died, but even worse, that spiked his head on the gates of York, along with his father and uncle, who although seems disgusting enough to do to adults, it just seems unthinkable why it would be okay to do this to a seventeen year old boy, who according to Shakespeare, was allegedly fleeing at the time… when killed by Lord Clifford, or so the story goes…which is probably not entirely accurate. But I also read a contemporary primary account about how during Richard III’s short reign, he re-interred his brother, Edmund, along with his father with much fanfare, and the accounts claim it was very grand with a huge feast served, but also very solemn, and that he read speeches about his brother and father and it said that Richard III even wept during the re-interment ceremony. However, in regards to your Plantagenet pedigree info, you made a couple mistakes, so wanted to point out a couple corrections to your facts on the ancestry of the Plantagenet Kings and Dukes. Edmund of Langley, Duke of York, was not a son of King Edward II. He was son of King Edward III. King Edward II only had two legitimate sons, King Edward III and John of Eltham, Earl of Cornwall, who died at the age of 20 sans issue (there’s also a third illegitimate son, Adam Fitzroy). Edmund of Langley was the 4th surviving son out of 5 surviving sons of King Edward III, so is also not Edward III’s youngest surviving son either, as that was Thomas of Woodstock, Duke of Gloucester. The sons of Edward III in order from oldest to youngest were: (1) Edward the Black Prince (b. 1330, d. 1378 of illness); (2) Lionel of Antwerp, Duke of Clarence (b. 1338, d. 1368 in Italy, possibly poisoned–he was also rumored to be a nearly 7 ft tall); (3) John of Gaunt, Duke of Lancaster (b. 1340, d. 1399 of illness–House of Lancaster namesake); (4) Edmund of Langley, Duke of York (b. 1341, d. 1402 at home, probably of illness–House of York namesake ); and finally (5) Thomas of Woodstock, Duke of Gloucester, who not only was the youngest son, but also the youngest child of Edward III (b. 1355, d. 1397, murdered by Thomas Mowbray, after imprisoned by his nephew, King Richard II, for alleged treason). And although Thomas of Woodstock was murdered, he was 42 at the time of his death, and so definitely survived to adulthood. He also married Eleanor de Bohun, who he had issue with and has many descendants alive today. I know because I am one those descendants via their daughter, Ann Plantagenet. But great article, thanks for posting this about Edmund, it’s good to see him getting some recognition, most television and movies and such, ignore him, as though he never existed, and if he was old enough to have his head spiked, he’s worthy of being mentioned in history, in my opinion.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you, Lisa. Very informative, and well done for finding the illustration. Quite a feather in your cap.

LikeLike

This number of mistakes would probably be worth a thorough correction of the article itself. I have always been fascinated by anything Plantagenet (and of course Lancaster and York), and I was googling Edmund of Langley’s (1st Duke of York) appearance, when I got here and read the article. I had to double-check all the genealogical facts because at first I didn’t suppose the 2nd paragraph of a serious article can be so wrong. BTW I’m still looking for info about the said Edmund’s appearance :).

LikeLiked by 1 person