Tapestry executed by William Morris, after Sir Edward Burne-Jones

According to the Oxford Dictionary, the following two definitions refer to the use of the word epiphany:-

- The manifestation of Christ to the Gentiles as represented by the Magi (Matthew 2:1–12). Definition (1)

- A moment of sudden and great revelation/realisation. Definition (2)

Epiphany has been a recognised feast of the Western Church since the 5th century, but these days we generally associate the Magi/ Three Wise Men with our modern Christmas Eve/Day. They appear on our Christmas cards. Yet there are—and always were—Twelve Days of Christmas, with Twelfth Night marked as Epiphany Eve or sometimes Epiphany itself, depending upon which precise moment you begin to calculate the commencement of the season. For an explanation, this is a good place to start.

If ever there was a King of England who revered Epiphany (1), and all that went with it, that king was Richard II, who reigned 1377-1399. He was still a small boy, but when the Yule logs were brought in for the first Christmas of his reign, they must have been kindled with hope and excitement that he would bring health, wealth, happiness and prosperity to his new realm. If this was indeed the hope, there would eventually be some very unhappy people, because he was plagued by rebellions and resentful lords. And his habit of turning to a coterie of close friends, twinned with his own questionable decision-making, did not really create the best circumstances. But, initially, there was hope, and those first Yule logs of 1377 will have burned brightly. The flames would have danced and roared.

That fanciful thought aside, it is my opinion that in June 1381, when as a boy of only fourteen Richard faced a thousands-strong army of peasants at Smithfield, he underwent an epiphany (2). He rode out at the head of his retinue to face a ragtaggle peasant army led, among others, by Wat Tyler. We all know the famous scene. Tyler was cut down in front of everyone by Sir William Walworth, Mayor of London, and out of nowhere the moment became electrifyingly dangerous. Pitched battle was on the very lip of breaking out, but then Richard rode his horse forward calmly and promised to do all he could to grant the peasants’ their demands (which we today think were more than justified). It worked and the peasant army broke up to return to their homes.

Richard later went back on his word (something he was prone to do throughout his reign) but at that precise moment he’d displayed astonishing courage, and split-second decision-making. No one else in his entourage had done anything but freeze. Many things about the adult Richard II were to be criticized, but never again would his courage be questioned. Did he have an epiphany, as described in (2) above?

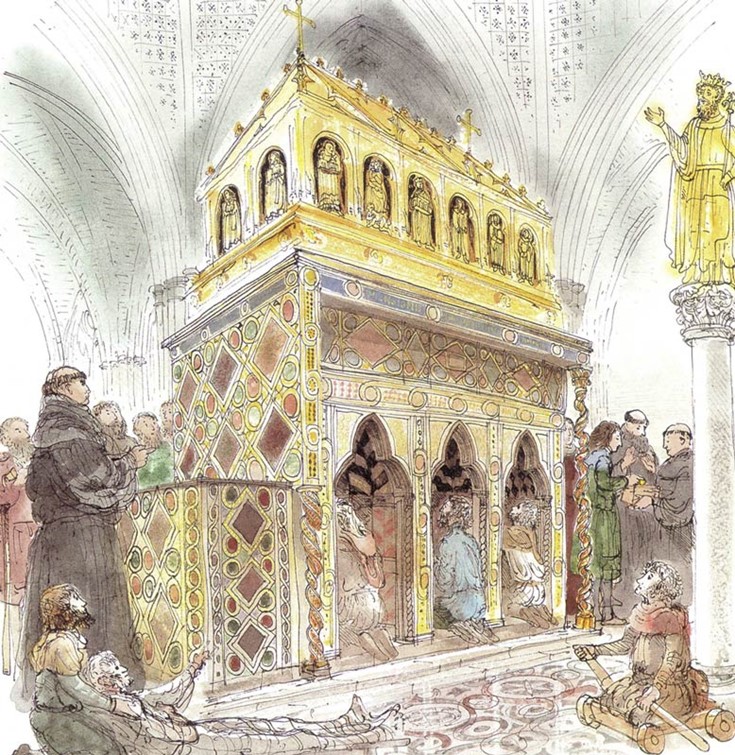

Certainly he was always to honour Epiphany above all other Church festivals. To begin with, he was born on that day in 1367. Another King of England who was buried on that day in 1066 was to become Richard’s favourite and most cherished saint. That king was St Edward the Confessor, whose feast day is 6th January/Epiphany, and whose great tomb in Westminster Abbey can still be seen. It’s now a shadow of its former glory because all the jewels and other decorations that once adorned it have been gradually stolen over the centuries by all forms of souvenir-seeker. But it must once have been a glorious sight, as was St Thomas à Becket’s tomb in Canterbury, which has been similarly denuded.

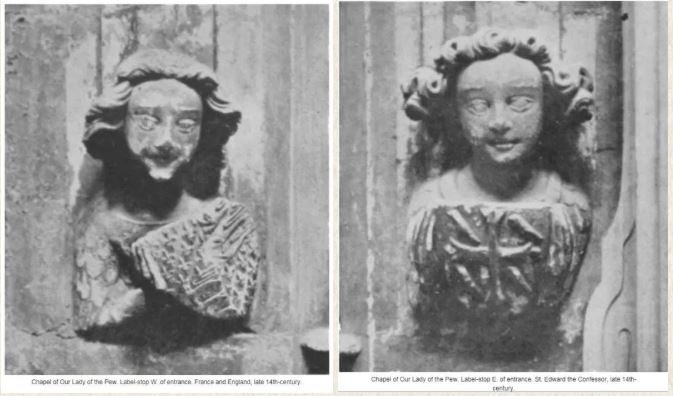

The Confessor had been England’s national saint until 1350, when he was supplanted by St George, and on Epiphany every year, Richard II went to worship there, usually leaving a costly gift. Such occasions must have been very impressive and colourful. Richard also had a separate little chapel built nearby, where he would worship. It is still called the Chapel of Our Lady of the Pew, and contains a niche in the wall where it is said the wonderful Wilton Diptych was placed for Richard’s prayers.

The diptych shows Richard as a child king, with St John the Baptist, St Edward the Confessor and St Edmund standing behind him as he kneels before the Virgin and Child. At the entrance of the chapel are two carved headstops of angels, one holding Richard’s royal arms, the other those of the Confesser. (Pingback https://murreyandblue.wordpress.com/2017/07/15/the-little-chapel-in-westminster-abbey-beloved-of-richard-ii/)

According to https://www.britainexpress.com/History/medieval/christmas.htm , another link between Richard II and Epiphany occurred on Twelfth Night, 1392. The citizens of London, who were not on good terms with him at the time, attempted to bury the hatchet by bestowing upon the king and queen “a one-humped camel and a pelican, novelties for the royal menagerie at the Tower of London”. Another source adds that there was a boy on the dromedary.

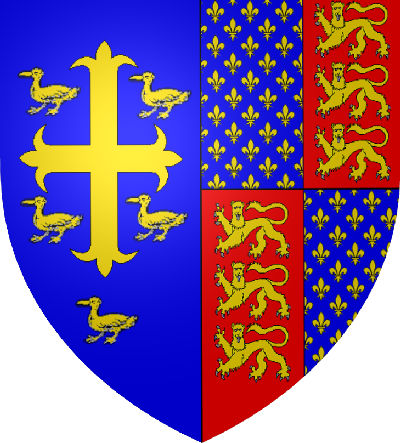

Richard and his much loved queen Anne of Bohemia would eventually be laid to rest together close to the Confessor. In the latter part of his reign, Richard had even had his own coat-of-arms impaled with the supposed arms of the Confessor, so there is no doubt at all that Richard II truly esteemed Epiphany and the Confessor, with whom he felt a close connection.

To the less religiously minded people of today, Epiphany is Twelfth Night, a time to party and take the Christmas decorations down – if they haven’t been removed already! The more devout will still associate it with the Magi and the Confessor.

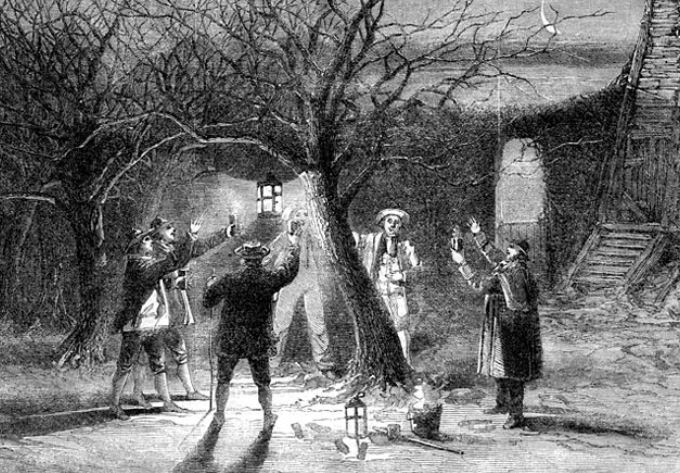

Of course, the calendar has changed from Julian to Gregorian, and dates have moved with it. Old Twelfth Night was celebrated on 17th January. Many wassail traditions, such as the wassail cup and wassailing the cider apple trees, are associated with Twelfth Night. The Yule Log, so bright with flames in the image above, needs to burn from Christmas Eve until Twelfth Night. Charcoal from it was kept to kindle the following year’s log, and also to protect the house from thunder and lightning. There were also many delicious foods that were associated with that night, including a special cake.

In many places across the land older customs have been resumed in recent years. I don’t know when in the past they began to wassail the cider apple trees, in the hope of ensuring a supply of cider for the next harvest. Does it go back to the medieval period? Yes, according to this article

“….There are two distinct variations of wassailing. One involves groups of merrymakers going from one house to another, wassail bowl in hand, singing traditional songs and generally spreading fun and good wishes. The other form of wassailing is generally practiced in the countryside, particularly in fruit growing regions, where it is the trees that are blessed….”

“….The practice of house-wassailing continued in England throughout the Middle Ages, adapting as a way by which the feudal lord of the manor could demonstrate charitable seasonal goodwill to those who served him, by gifting money and food in exchange for the wassailers blessing and songs….”

Singing from house-to-house eventually became the carol-singing of today, but at the end of the season, not the beginning. As happens now with the Three Wise Men, who appear of Christmas cards, but are actually associated with Epiphany.

Now, to go back to the very beginning of this article, and the epiphany (2) that I feel certain happened to the young Richard II in June 1381. Until that day in Smithfield he had been confined and controlled by his uncles and government, but when Tyler was cut down in front of everyone and things turned very nasty indeed, Richard stepped into the breach by calmly taking charge.

From where did that sudden steely resolve come? He hadn’t displayed any such thing before, but….did he think of Epiphany? His day? When the Magi took gifts to the Christ Child? Did he suddenly see himself as a Christ Child too? Born to reign over all? Did he begin to understand that it was his God-given right by blood to cast aside the oppressive rule of his uncles and their government? Might such a heartstopping moment of insight been the reason for the Wilton Diptych, which shows him as a boy (when he was adult by then) anointed and royal, reaching out to accept something from the Christ Child. The reins of his kingdom, perhaps? Was this his epiphany (2)? Albeit in June.

Afterwards, in quiet moments, did he sit alone and pensive, considering who he was and how he should face the future?

It was to be another eight years before he was finally able to strike free of those who sought to keep him under their control, but I believe his first realisation of his true destiny was born that day in Smithfield.

Epiphany had one more vital role to play in Richard’s life, and that was in 1400, just after his cousin, Henry of Lancaster, had usurped the throne and consigned Richard to captivity in Pontefract. Epiphany was the date chosen by Richard’s desperate supporters to fight against the new regime and restore him to his throne.

Known as the Epiphany Rising, this revolt was doomed to defeat because of treachery within its ranks. And the eventual result was Richard’s probable murder at Pontefract, to prevent any more attempts to restore him. At least he didn’t die on Epiphany as well, but he was laid to rest on the 6th…of March, 1400.

His Twelfth Night was at an end. The bright Yule log had finally run its course, flickered and faded.

2 comments