Well, we’ve all heard of the “Abbey of the Minoresses of St. Clare without Aldgate known also variously as the ‘Abbey of the Blessed Virgin Mary, Aldgate’ or the ‘House of Minoresses of the Order of St Clare of the Grace of the Blessed Virgin Mary’ or the ‘Minoresses without Aldgate’ or ‘St Clare outside Aldgate’ or the ‘Minories, London’” was a monastery of Franciscan women living an enclosed life, established in the late 13th century on a site often said to be of five acres, though it may have been as little as half that, at the spot in the parish of St Botolph outside the medieval walls of the City of London at Aldgate that later, by a corruption of the term minoresses, became known as The Minories, a place name found also in other English towns including Birmingham, Colchester, Newcastle upon Tyne and Stratford-upon-Avon…” The above extract is taken from the Wikipedia page.

It became a very sought-after refuge for highborn women who no longer wished to be regarded as being “in the market” for marriage – see here for instance. No doubt there were other reasons too, but at one time the abduction and forced marriage of women by men intent upon their fortunes was rather commonplace.

Women felt safe in abbeys and such life, where they were surrounded by other women. Not that this chosen seclusion actually made them safe, as the case of Sir John Sandys, who in 1375 abducted “the recently widowed Joan Bridges from Romsey Abbey (Hampshire), where she had been staying.” For more of this, see this Northants site.

But given this story, and others, it’s not surprising women huddled in abbeys like hens in a coop. I would have too. But, as we all know, the fox can still break into the feather-filled sanctuary!

Thomas of Woodstock, Duke of Gloucester, youngest son of Edward III, wasn’t such a fox, I hasten to point out, but he managed to have a house built at the Minories, with a connecting door into the church. He placed his youngest daughter, Isabel, in the Abbey and she eventually became the abbess.

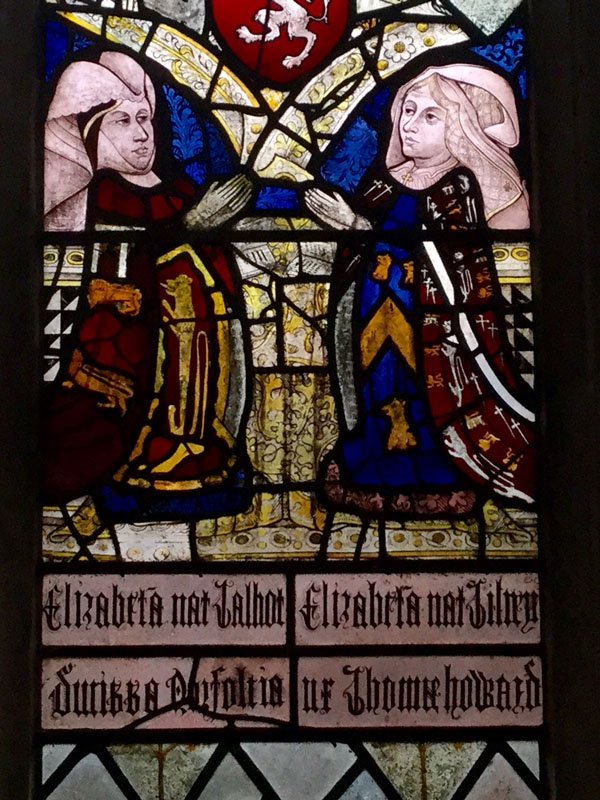

Elizabeth Talbot, Duchess of Norfolk, lived there and was also buried there. She was the younger sister of Eleanor Talbot, first wife of Edward IV. Her only child, Anne Mowbray, was buried at the Minories. She’d been the small wife of the almost equally small Richard, Duke of York, younger of the two boys of Tower fame.

Elizabeth Tilney, Countess of Surrey was buried there. Her husband was Thomas Howard, who was restored to his father’s (d. 22.8.1485 fighting for Richard III) forfeited dukedom after Elizabeth’s death.

Anne Beauchamp, wife of the 12th Earl of Warwick, resided there, and so on. She was the mother of Richard III’s queen, Anne Neville. I’m sure there are some very important ladies I’ve omitted, but this article isn’t about them wanting to live in the abbey, it’s about one of the nuns wanting to get out!

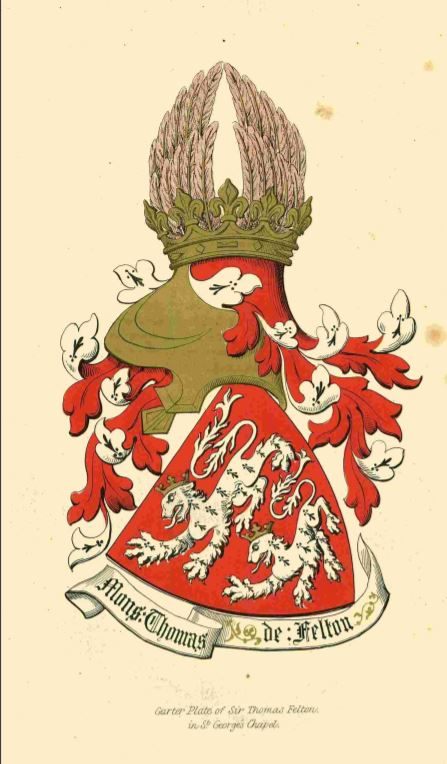

Not all daughters placed in the abbey by their parents were happy about it. Once such was Mary Felton, whose father was Sir Thomas Felton, an early Knight of the Garter who died very shortly after his installation in 1381. That’s another story. Suffice it that Mary ended up at the Minories. But that was after three marriages.

Not that she’d known much about the first, to Edmund Hengrave of Hengrave, Suffolk. She was an infant, and he died abroad in 1374. That same year she was married to her second husband, Sir Geoffrey Worsley. He seems to have died soon after, because in 1376 she was married for the third time to Sir Thomas de Breton. Oh, but then it was found that Sir Geoffrey, who’d been a prisoner-of-war in Spain, hadn’t died after all, so the third marriage was invalid. Exit Thomas de Breton, unmarried.

Mary’s father died early in 1381. So there was Mary Felton, with three marriages under her belt, or perhaps only two. At this point there are certain allegations made about her, um, faithfulness. Sir Geoffrey wasn’t happy about the shenanigans while he’d been banged up and accused the very servant he’d placed to guard Mary while he, Geoffrey, went off to war. The servant was a certain Thomas Pulle, and Geoffrey accused him of not only “dishonouring” her, but of marrying her too. A fourth marriage?

Sir Geoffrey was not happy, and set about Pulle, injuring him so badly that Pulle later died. Geoffrey petitioned that he, Geoffrey, wasn’t responsible for the death. Then he “divorced” Mary and married someone else, a lady name Isabel de Lathom and in 1383 they had a daughter, Elizabeth. He died early in 1385.

So where does all this leave Mary? Well, by 1383 she seems to have had enough of this marriage lark and entered the Minories. Then, at the end of 1385, there’s a warrant for her arrest! She’s described as an “apostate vagabond sister” and is to be returned to the abbess for punishment.

Another petition appears, this time from Sir Robert de Worsley, who was guardian of the late Geoffrey’s daughter, Elizabeth.

It seems that Mary had run away from the abbey claiming that she’d been forced to enter in the first place. Now she had begun proceedings to reverse her “divorce” from Sir Geoffrey. If successful, she would render young Elizabeth baseborn and thus disinherit her. Sir Geoffrey’s kinfolk would get his inheritance instead.

For the final outcome of Mary’s very tangled life, go to Medievalists Oh, but by the way, she did marry again (although whether it was the fourth or fifth time I’m not entirely sure – did Thomas Pulle count?) to a certain Sir John Curson, who just happened to deal with all her court proceedings. The abbess didn’t get her hands on the “vagabond”, and it seems that even after all the foregoing, Mary wasn’t put off holy matrimony. But at least we can be fairly sure that the last venture was probably of her own volition. I think.

1 comment